At last, after all the doubts and all the obstacles, Rudy Tomjanovich had made it.

The San Diego Rockets made him the second pick of the 1970 NBA draft, taken ahead of future Hall of Famers Pete Maravich and Dave Cowens. He had made it out of Hamtramck, Mich., become an All American, and been given a rich new NBA contract.

Again, as always, he would face doubts and obstacles anyway.

For reasons few understood at the time and Tomjanovich dismisses still as just “political,” Rockets coach Alex Hannum rarely played his rookie forward. Tomjanovich wrote in his autobiography that he would learn years later Hannum had wanted to trade Elvin Hayes and that when he did not get his wish, he used his rookie forward, taken second in the draft, as leverage. Others had assumed Hannum disagreed with the choice in the draft. Either way, Tomjanovich averaged just 13.8 minutes and 5.3 points per game in that rookie season.

“I couldn’t understand why Alex Hannum didn’t treat Rudy with respect,” said Calvin Murphy, who was selected by the Rockets in the same draft and would become Tomjanovich’s roommate and predecessor in the Hall of Fame. “I understand now it was all politics. He wanted somebody else, and the franchise took Rudy. But when we got together in rookie camp, I saw his potential. As the years went on, he proved what I knew from the beginning. And I’m not talking as a great friend and roommate. I’m talking as a guy that knows basketball.”

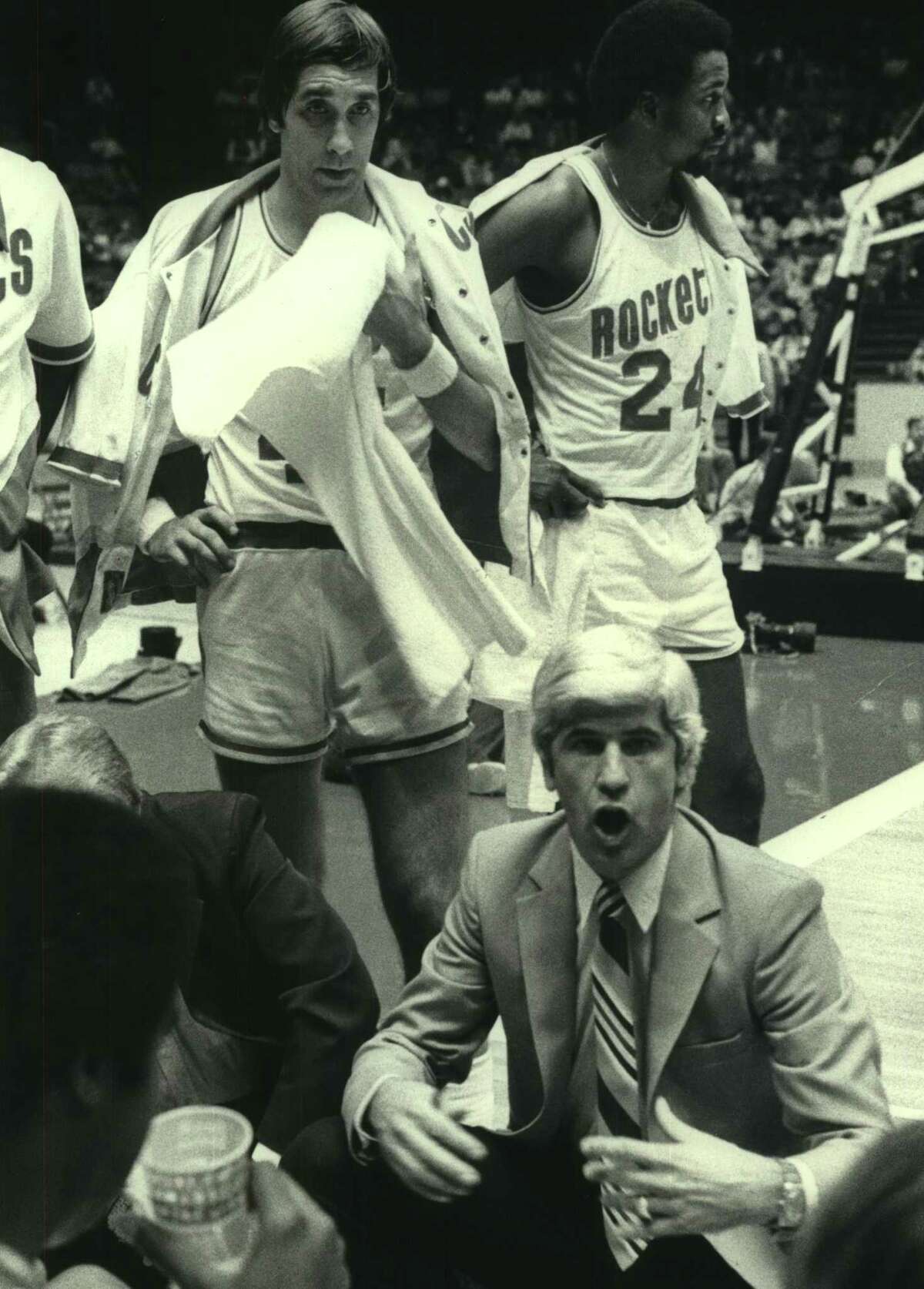

When the Rockets were sold and moved to Houston, Tomjanovich got his break. Tex Winter became coach, not only elevating Tomjanovich’s role but teaching him about the value of spacing, which would become central to Tomjanovich’s widely emulated coaching concepts decades later.

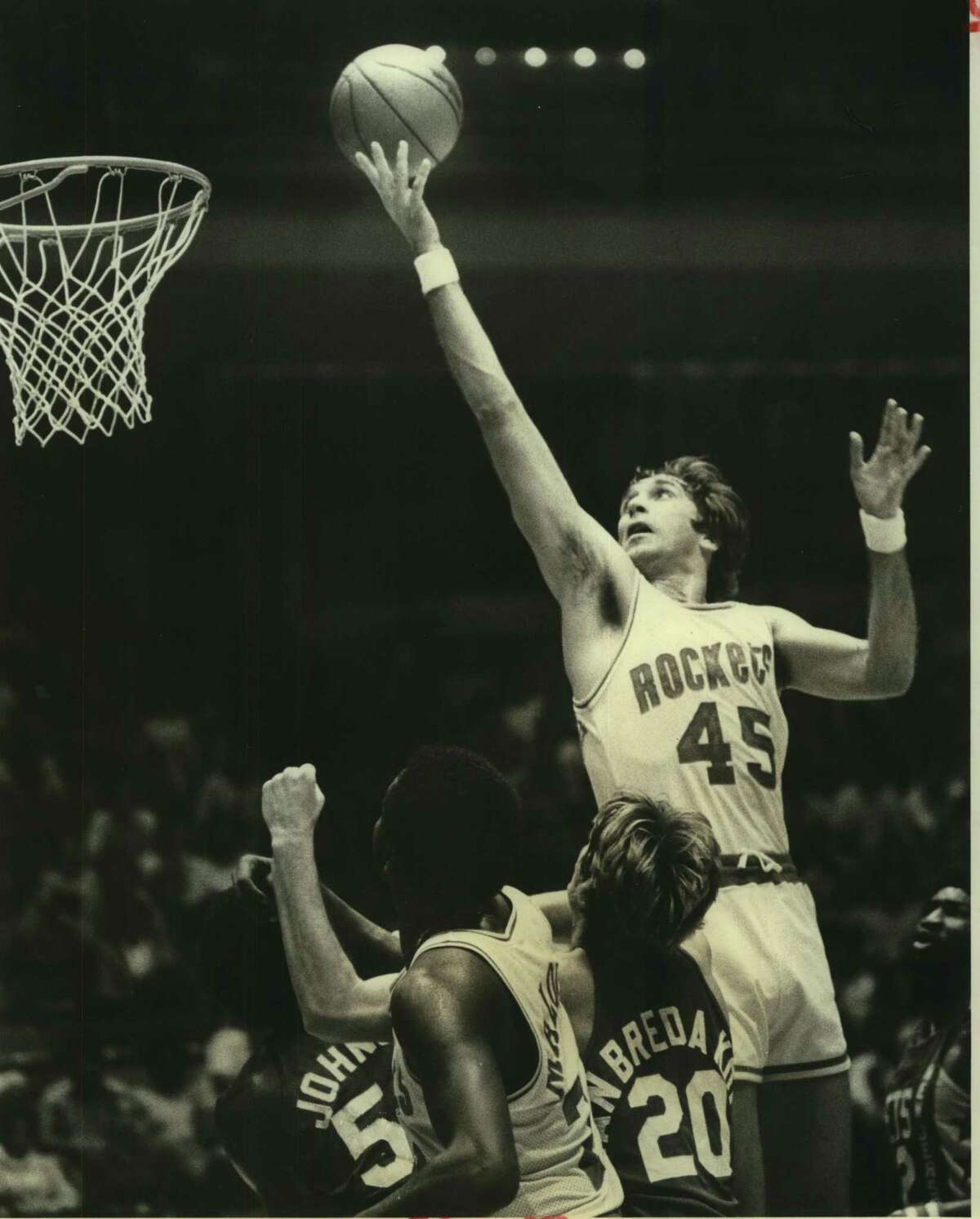

Tomjanovich averaged 15 points and 11.8 rebounds that season, 19.3 and 11.6 the next. By his fourth season, his third in Houston and the first under Johnny Egan as coach, he averaged a career-best 24.5 points per game and made his first of four consecutive All-Star Games.

“Rudy mentally was a winner,” Murphy said. “He knew how and could do all the things to make a team be a consistent winner. And we had average teams.”

Tomjanovich had first seen Murphy at a holiday tournament at the University of Detroit. He and Michigan teammates went to the game just to see the Niagara guard. Doubts about Murphy’s potential at 5-9 allowed him to slide to the second round and join Tomjanovich in San Diego. They became roommates when Murphy tired of veteran Larry Siegfried’s giving him the rookie treatment, and as much as they seemed the Odd Couple, as they called themselves, both were incredibly driven to overcome obstacles.

“If you room with him and spent 10 years talking basketball every night after every game, you’d know how driven he was,” Murphy said.

Told Tomjanovich said he became such a prolific rebounder because it was the only way to get the ball when on the floor with Hayes, Murphy and Stu Lantz, Murphy said, “He’s also full of it.

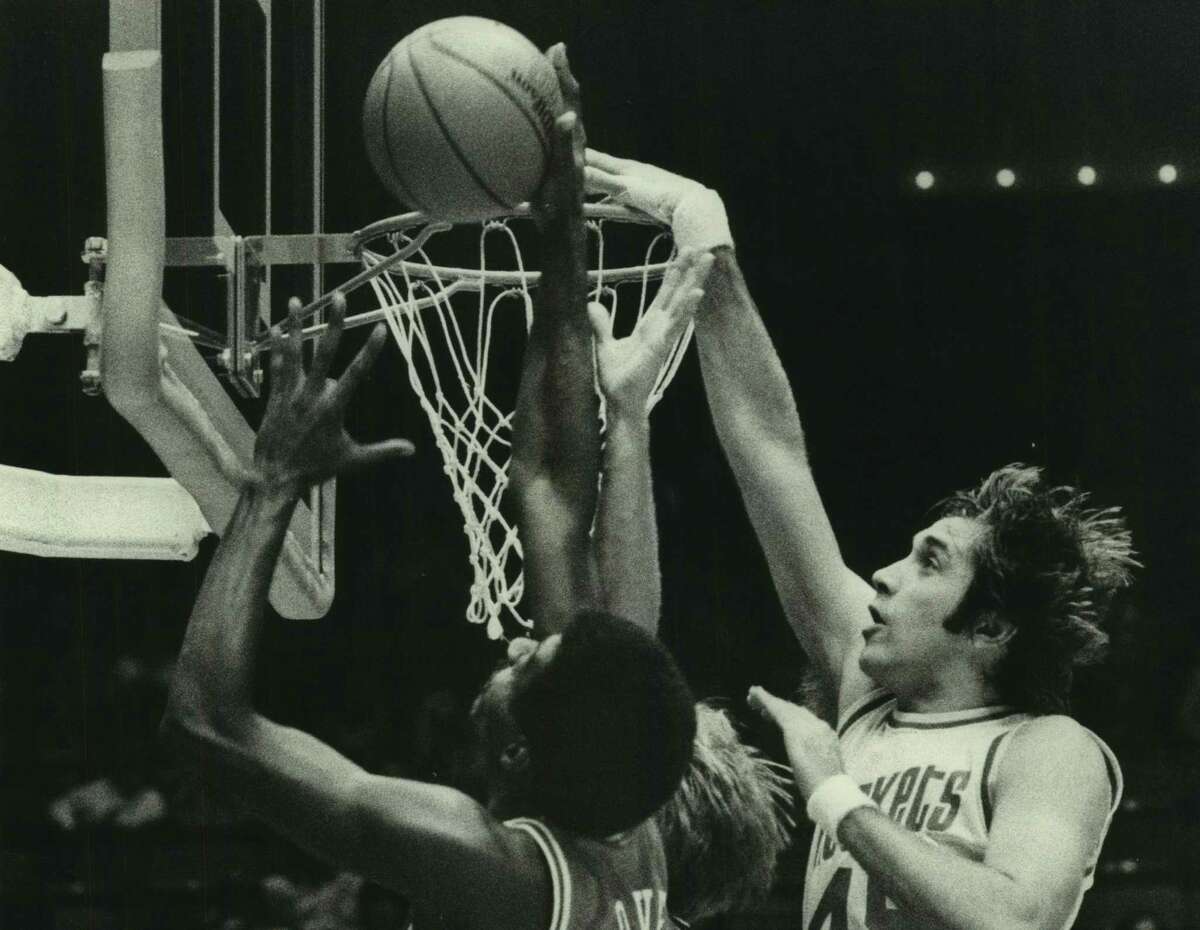

“One thing I did: I made sure when I needed an assist, I’d get the ball to Rudy. He was a pure shooter, not just a scorer. He was a pure shooter. We spent countless hours of practice time working out. He was just as good or better than me as a pure shooter. Other than Sam Jones of the Boston Celtics, Rudy had the greatest bank shot in the history of the game, no question. He was a tenacious rebounder. Rudy did whatever he had to do to get that ball.”

Hayes was traded after the Rockets’ first season in Houston, 1971-72. The Rockets would be built around Tomjanovich, Murphy and Mike Newlin, adding Moses Malone and John Lucas in 1976-77, their first winning season.

“I played with him almost 10 years,” Newlin said of Tomjanovich. “There never was a day he didn’t give 115 percent. There wasn’t a practice, there wasn’t a bus ride, there was nothing that he didn’t give 100 percent, and when I mean 100 percent, I mean neurotically 100 percent. Calvin Murphy was the same way.

“He was also the purest bank shooter of all time. He was the most affable teammate you ever could have. He was everybody’s best friend in a humble, shy sort of way. He was a tenacious offensive player, a consummate team player, and prepared for every game. I don’t know what better you can say about a guy than to say you could count on him every single night.”

Now Playing:

Tomjanovich had all that going for him when the Rockets played the Lakers in The Forum on Dec. 9, 1977. Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Rockets center Kevin Kunnert became tangled, and players rushed toward them, Tomjanovich reaching them first. Lakers forward Kermit Washington turned, saw Tomjanovich, and threw a straight right hand that landed just below Tomjanovich’s nose.

Tomjanovich fell to the court, blood gushing, his face shattered in four places. At the hospital, he was told the bitter taste in his mouth was spinal fluid leaking from his brain. This was no broken nose. His injury was life-threatening.

Of all the obstacles Tomjanovich had overcome, none could compare.

He was back the next season, played 81 games, averaged 21.6 points, and was voted in as an All-Star.

“He operated maniacally as if he was driven by a fear of failure,” Newlin said. “He operated like he was fighting for his life all the time.”

“That was just Rudy,” Murphy said. “Another thing Rudy and I had alike was our determination not to be defeated. It used to tickle me, because people said that punch killed his career. That was not true, because when he came back, his statistics were as good or better than before he got hit. He still had the same attitude, the same tenaciousness.”

Tomjanovich was ambivalent about the All-Star selection, however, believing it was at least to some degree given because of what had happened. But nothing could have been more of a statement than to return to the All-Star Game the year after the punch and to play again in Detroit, his hometown.

“I didn’t want to accept it,” Tomjanovich said. “It was a year after that. I had never gotten voted in. I got voted in that year to start that game. I didn’t feel I was worthy of it at that time. I still thought I could make the team, but I thought that wasn’t right. I talked to a couple people, and they convinced me (to) go ahead and do it with a clear mind. And I did, and it was one of my better All-Star Games.”

Tomjanovich played just two more seasons, with his role and playing time diminishing to the point he rarely played in the 1981 run to the NBA Finals.

There were rumors he would be traded. Tom Nissalke, the Rockets’ coach from 1976 to 1979, had become the Jazz coach. Tomjanovich decided he did not want to move his young family or play for another team. With two guaranteed years left on his contract, he and Rockets president Ray Patterson negotiated a deal with Tomjanovich paid for one season and forfeiting the second.

After 11 seasons, five All-Star appearances, averages of 17.4 points and 8.1 rebounds, and having gone from San Diego to the barnstorming days playing home games around Texas and in The Summit, Tomjanovich retired at 32 with no regrets and no idea where his second career would take him.

"all" - Google News

May 09, 2021 at 04:05PM

https://ift.tt/3f3zToy

Rudy T: The makeup of a five-time All-Star - Houston Chronicle

"all" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2vcMBhz

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Rudy T: The makeup of a five-time All-Star - Houston Chronicle"

Post a Comment